Childhood tics are more common than you might think

During the first lockdown, my daughter’s eyes began darting to the left, over and over again. Not long after that, she started clearing her throat repeatedly and her left index finger began to twitch. Once doctors ruled out an eye or brain disorder, we learned that she had tics—a surprisingly common childhood experience that we really didn’t know that much about.

It turns out up to 20% of school-aged kids experience tics, but at least half outgrow them by adulthood, according to the Tourette Association of America. A smaller number—less than 1% of children—will still experience tics adults.

“It’s more common than most people realize,” says Pediatric neurologist Dr. Mered Parnes, who leads the Pediatric Movement Disorders Program at Texas Children’s Hospital. Fortunately, tics don’t usually cause discomfort. “The majority of people who have tics, I would imagine, would never come to medical attention because they’re mild or at least manageable.”

Here’s what else you should know about tics in kids.

What are tics and what do they look like?

Tics are brief, repetitive, and purposeless movements (motor tics) or sounds (vocal or phonic tics) that typically start when a child is between the ages of four and eight.

Motor tics can take many forms, including:

- Grimacing

- Blinking

- Rapid jerking of a body part

- Arm or hand movements

- Nose twitching

- Shrugging

- Eye movements

Vocal or phonic tics also vary and may include:

- Throat clearing

- Repeating sounds or phrases

- Animal noises

- Grunting

- Coughing

Parnes stresses that it’s rare for people with tics to make profane gestures (copropraxia) or utterances (coprolalia). “The words ‘Tourette Syndrome’ can induce a lot of anxiety for parents because they think about what they see in movies,” he says. “They think about screaming, and they think of obscenities.” In reality, tics and tic disorders seldom resemble the stereotypes in popular culture.

Could my child have a tic disorder?

Most of the time, tics are transient—that is, they come on suddenly and disappear just as quickly. But when tics persist, a kid may be diagnosed with one of three neurodevelopmental disorders:

- Provisional Tic Disorder: children with one or more motor or vocal tics for less than a year.

- Persistent/Chronic Tic Disorder: kids who have had one or more motor or vocal tics—but not both—almost every day for more than a year.

- Tourette Syndrome (TS): children who’ve had both motor and vocal tics almost every day for more than a year.

As littles grow their tics will often subside or disappear. About one-third of those diagnosed with TS will have no tics by early adulthood, and another one-third will have fewer or milder tics.

What causes tics in kids?

We don’t know exactly what causes tics, says Parnes. However, we do know that tics and tic disorders stem from a genetic, brain-based difference related to how messages travel between three areas of the brain: the thalamus, basal ganglia, and cortex. We also know that dopamine, a neurotransmitter used by the nervous system to send messages, plays an important role.

Related: Billie Eilish on Living With Tourette’s: ‘I’m Very Happy Talking About It’

Research shows that 83% of children with TS have also been diagnosed with another disorder—about one-half have Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and one-third have Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

But the most common comorbidity is anxiety, which can worsen tics. During stressful times—the night before a spelling test or the week before school starts—kids tend to experience a lot more tics.

Can children ‘catch’ tics?

A tic disorder isn’t contagious like a cold or flu, but on rare occasions, tic-like behaviors seem to be socially contagious. In 2012, 19 teenagers in the LeRoy Central School District in northwestern New York began exhibiting symptoms of TS. And during the pandemic, when social media use and anxiety surged, doctors worldwide saw a record number of patients complaining of tics. Parnes wrote a research paper about teen girls developing tics after watching TikTok videos featuring users with tics.

Some think that pandemic stress and social media use contributed to a kind of mass social contagion, says Parnes. But rather than ‘catching’ a tic disorder, these teens more likely experienced tic-like movements caused by Functional Neurologic Symptom Disorder (FND), which is when neurological symptoms appear in the absence of any disease or disorder.

What treatment options are available for childhood tics?

Sometimes, tics can be bothersome or even debilitating. Forceful neck and eye movements can cause chronic headaches or, in rare cases, even spinal injury. Tics involving the arms or hands may prevent kids from playing sports and intense eye-blinking may interfere with schoolwork.

For kids whose tics are impairing in some way, treatment may be necessary and can include:

- Oral medications, such as alpha-2 agonists (like clonidine and guanfacine) and dopamine-receptor blocking agents (like fluphenazine and risperidone).

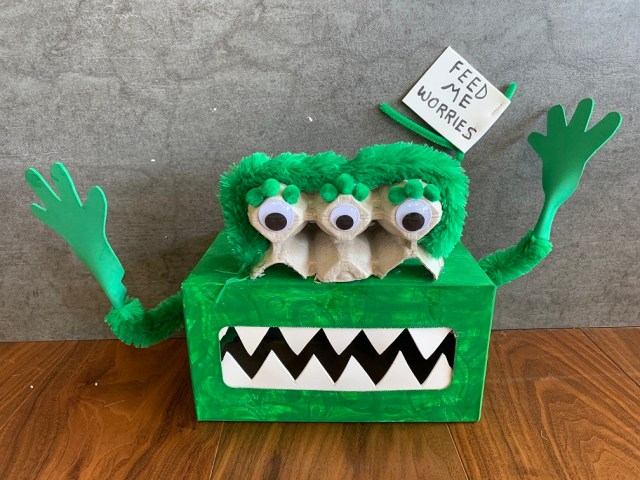

- Behavioral therapy like Comprehensive Behavioural Intervention for Tics (CBIT), which teaches children and teens to channel the urge to tic into different behaviors.

Parnes says there isn’t scientific evidence to suggest that patients benefit from dietary changes, vitamin supplements, or other lifestyle interventions.

Are there other ways to support kids with tics?

TS is a stigmatized diagnosis. Parents can help de-stigmatize the disorder by speaking openly about TS with their children and ensuring they have as much information as possible. “We want [parents] to acknowledge that this is normal for them—it’s just like hair color or eye color,” says Parnes. “It’s just part of the way they were made.”