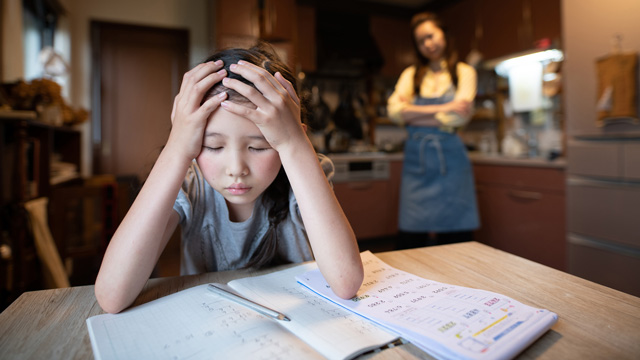

Ask any parent what it’s like to raise a kid today, and we’d likely tell you modern childhood seems much more complex—and perilous—than when we were young. Thanks to increased peer pressure, massive technological advances, and on-demand access to virtually anything via click or tap, kids today face a wider array of choices and decision-making opportunities than we did when we were their age.

As parents, we hope we’ve instilled strong values and resilience in our children so they’re always able to make good decisions. But how can we be sure they’ll do the right thing, especially when we’re not around? While there’s no magic formula, here are 10 tips to help your kid make smart decisions—even when you’re not there.

1. Start conversations about smart decision-making early.

The earlier parents initiate conversations about how to make good decisions with their kids, the better. Explaining to your child what it means to make a good decision and why it’s important can set them up for future success. Kevin Zoromski, a psychologist and early childhood development expert says, “Give children choices as part of their day and as part of their typical routine. They will look forward to having some say over what they get to do in the household and you will establish their sense of responsibility as important decision-makers.”

2. Role-model smart decision-making behaviors.

Kids learn through observation and patterning the behaviors of people in their lives, especially their parents. Modeling good decision-making behavior will help reinforce your life lessons. Show your kid that you are honest, responsible, and accountable for your choices. “You are your child’s first and most important role model,” said mental health expert Ketsupa Jirakarn. “[Kids] are always observing and learning from you every day—even when you are unaware of it. So, make sure you practice what you preach.”

3. Set clear expectations and boundaries.

Let your kids know what you expect from them in terms of making smart decisions. For older kids, this could include things like always telling you where they are going, not using illicit substances like drugs and alcohol, and staying away from dangerous situations. “Children are more likely to accept the limits you set and are more likely to want to meet your expectations (i.e., be responsible) when you provide a warm, caring, and supportive relationship that underlies the discipline you impose,” according to a report from The Center for Parenting Education.

4. Practice makes perfect.

Give your child opportunities to practice smart decision-making. This could involve giving them small choices, such as what to wear to school or what to eat for dinner. It also could involve giving them bigger choices, such as whether to join a sports team or what to do with their allowance. By empowering your child to learn about the consequences of their choices through smaller actions, they will feel more empowered when making bigger decisions on their own.

Related: 8 Things Kids Need to Do By Themselves Before They’re 13

5. Let them learn from their mistakes.

When your kid makes a mistake, don’t immediately swoop in to fix the problem or resort immediately to punishment. Help them understand why a misstep was a consequence of not making the best decision, and then talk about how they can make a better choice next time. According to a report from the Harvard Graduate School of Education, “Reframing mistakes as opportunities from which we can learn—rather than failures alone—can help us feel like we are capable and in control. Reframing can also help us handle future mistakes more effectively.”

6. Develop their critical thinking skills.

Learning how to think critically and independently requires self-awareness (i.e., knowing strengths, weaknesses, and values) as well as problem-solving skills. Encouraging your child to think through a decision and come up with a solution can further nurture and develop their critical thinking skills. “In childhood and adolescence, the body goes through many physical changes, but there are also many changes in how we think, feel, and behave, and in our motivations,” according to a report from Frontiers for Young Minds. It’s through repeated trial and error that kids develop the necessary skills to thrive into adulthood.

7. Help them understand risks.

Some decisions have few consequences, while other decisions are highly consequential. Teaching your child the difference between big and small choices, and understanding the risks associated with some decisions will mitigate the chances of bad outcomes. For example, teach young kids about the risks of eating too much junk food or overdoing it with screen time, and teach older kids about the risks of cyberbullying and underage drinking.

8. Nurture emotional intelligence.

Talk to your child about the choices they’re facing and help them understand the different options and the potential consequences of each choice. Teaching them how to evaluate information, identify biases, and make informed decisions as well as helping your child understand and manage their emotions and how to make decisions that are in line with their values will serve them well. “Emotional literacy starts at birth when babies can just bond with [their parents] and connect on just that level. And it continues to evolve,” said Dr. Michele Borba, parenting expert and author of Building Moral Intelligence: The Seven Essential Virtues that Teach Kids to Do the Right Thing.

9. Be supportive and consistent.

As parents, being supportive and consistent with our reactions to our children’s choices will help ensure they make smart ones, even when we’re not present. If you sometimes let your child get away with making a bad decision, they will be less likely to take you seriously when you expect them to make good choices without you. Additionally, when your kid makes a good decision, be sure to praise and validate them. “Youth who experience more positive interactions with parents are better adjusted. Indeed, consistency in parenting—primarily consistency in discipline—has been linked to more positive youth outcomes,” according to a report from the National Institutes of Health.

10. Practice patience and understanding.

It takes time for kids to learn how to make smart decisions. Don’t get discouraged if they don’t always and immediately make the right choices. Even when your kids are old enough to make decisions themselves, they still need your patience and understanding. Be there to talk to them, offer advice, and help them deal with the consequences of their decisions.